By Cheyenne Ellis

NEIWPCC Environmental Analyst Victoria O’Neill has dedicated her career to researching and protecting the diverse habitats of Long Island. For the past 10 years, she has worked on countless projects in the field, as well as community outreach efforts which, as a native of the island herself, have given her the chance to pass her appreciation for the local environment to others.

O’Neill’s passion for restoration began in her childhood, exploring the marshes and beaches around her home in Suffolk County, New York. She developed a strong appreciation for nature and was devastated to learn how human actions threatened those ecosystems. Looking to protect the island where she was raised, O’Neill decided to major in biology at the State University of New York (SUNY) Geneseo; there, she fell in love with the field of ecology.

O’Neill spent her summers as an undergraduate working as a piping plover steward along the south shore of Long Island, where she monitored the nests of endangered shorebirds. In addition to keeping counts of adults, eggs and chicks using the site, she also informed the public about how to keep these birds safe. O’Neill enjoyed seeing her work reflected in the increasing nesting bird population counts.

She continued this line of research in her master’s program in biology at the College of William and Mary, focusing her studies on the nesting success of diamondback terrapins in the Chesapeake Bay. After graduation, she joined the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, later taking on the role of natural areas manager at Randall’s Island Park in New York City.

“I admittedly knew very little about the field when I started,” O’Neill said. “But I quickly learned how to restore habitat in one of the most urban environments in our country.”

O’Neill began her current position with NEIWPCC in 2013, working as a habitat restoration and stewardship coordinator for the Long Island Sound Study (LISS) out of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s (NYSDEC) office. When she headed back to Long Island, she noticed that the population had expanded substantially and areas that were once woodlands or farmland now contained large housing developments. The rapid expansion concerned O’Neill.

“With more people comes more pollution,” she said. “We have seen dramatic changes over the last few decades including more harmful algal blooms, declining wetland habitat and more public beach closures.”

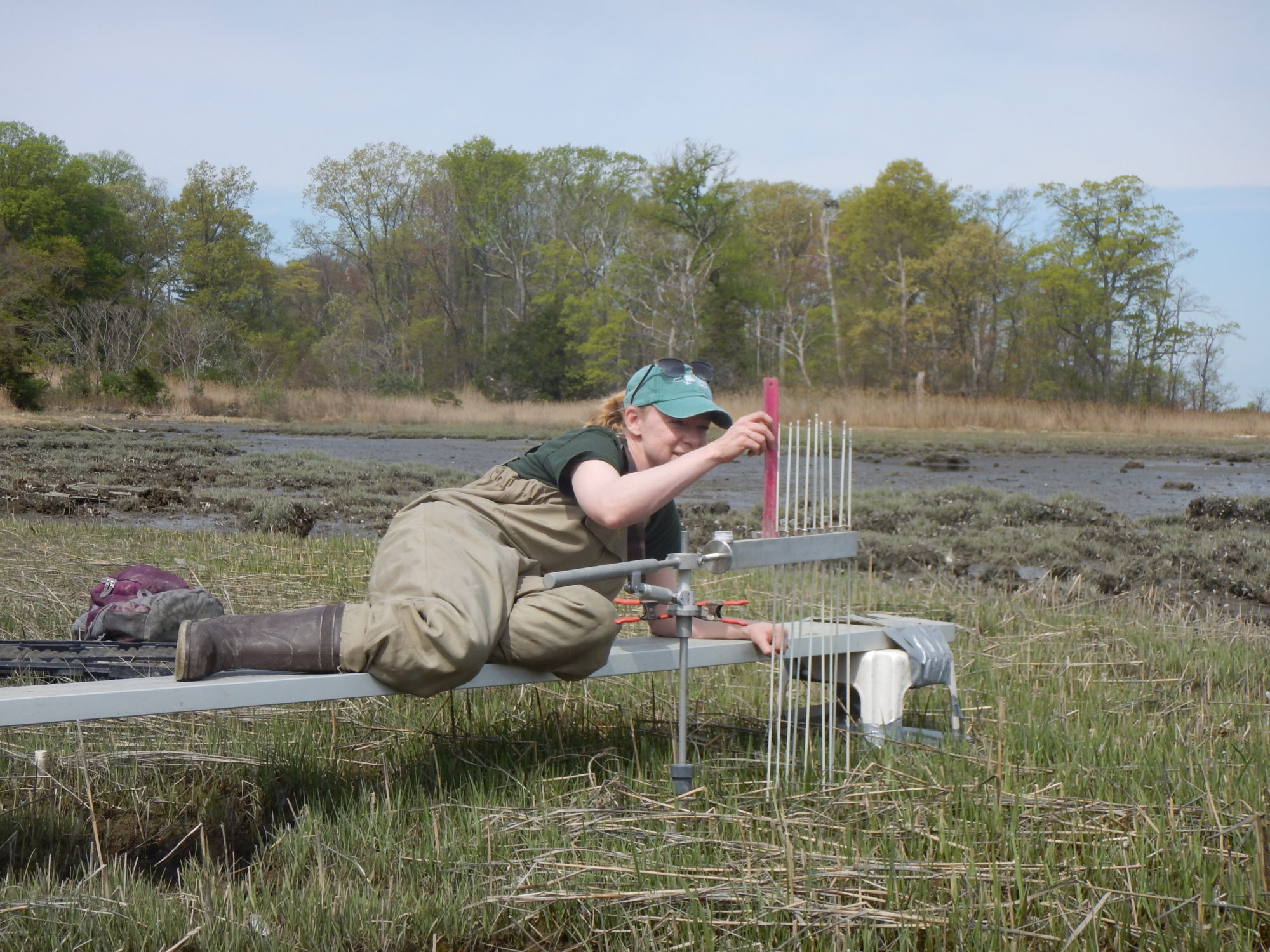

O’Neill now spends most of her time working to reverse these changes. In her position, she assists in everything from tidal wetland restoration to community outreach efforts. She also coordinates with other environmental science professionals from across the region to prepare and implement habitat restoration work plans.

“The best part of my job is working with so many different partners — no matter the organization, institution or agency, everyone is working to improve environmental health and water quality,” she said. “I feel that when I interact with other NEIWPCC employees across New England as well.”

Currently, she is serving as the project lead in an ongoing effort that involves analyzing 50 marsh complexes across the New York portion of Long Island Sound. The project will develop projections for each complex’s vulnerability to sea level rise, which is then stored on a mapping application called SLAMM (Sea Level Affecting Marshes Modeling).

Because of the uncertainty of sea level rise predictions, this program allows stakeholders to view each marshland under the lens of various scenarios — one filter shows the marsh under .43 meters of sea level rise by 2055; another shows the same marsh under 1.72 meters of sea level rise by 2100.

“The main users of the marsh viewer are municipal planners and environmental NGOs [non-governmental organizations],” said O’Neill. “Some of them have used the viewer to try and justify a marsh restoration. Others have used it to target land for conservation.”

A similar project is in progress by the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, which will complete the state’s portion of the marsh data for Long Island Sound. Data analysis wrapped up at the end of 2022 and O’Neill has now moved on to the outreach portion of the project.

She plans to create factsheets for each marsh complex, featuring easy-to-follow instructions for using SLAMM which will be available both online and in print for stakeholders at various events. O’Neill will also lead a workshop for those who are unfamiliar with online mapping programs. Her goal is to work closely with interested communities to create long-lasting conservation plans.

“I learned very early on that you must include members of the community in your projects,” she said. “People care about what is happening in their communities and they want to have a say in what their communities will look like in the future.”

O’Neill is also involved with a newer coastal management strategy called living shorelines, which uses natural materials like vegetation, rocks, sand and aquatic organisms to protect coastal marshlands against the effects of sea level rise. Living shorelines have become more common in Connecticut following the successful completion of the Stratford Point Living Shoreline in 2014. The pace of restoration has been slower along the north shore of Long Island where O’Neill is assisting with the Edith Read Living Shoreline in Rye, one of the only projects under way in the area.

“People are hesitant to build living shorelines because there are limited examples available,” O’Neill said. “They can also be quite difficult for the public to understand.”

She hopes to change these perceptions by bringing education about living shorelines directly to communities. Through webinars, interested parties can hear from experts, see examples of local projects and find resources to plan a living shoreline on their land. In addition, she works closely with five sustainable and resilient communities extension professionals. LISS hired these specialists to help communicate climate change and mitigation strategies to those in their geographic area of service.

In addition to her efforts around habitat restoration, O’Neill frequently organizes field trips for groups of children, where she demonstrates water quality sampling techniques and introduces students to the field of ecology. She also runs a partnership with Seatuck Environmental Association, recruiting and training volunteers to monitor spawning alewife and eels. This program has led to the discovery of new fish runs.

Despite so many accomplishments, O’Neill is always eager to take on a new project. She is the co-chair of the Habitat Restoration and Stewardship Workgroup for LISS which meets four times per year and was recently appointed co-chair of the Dam Removal Internal Working Group at the NYSDEC. She hopes to help organizations act quickly to take advantage of increased funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

“Removing a dam is a very complex process that requires lots of guidance and resources,” said O’Neill. “We hope to provide that support for the organizations we work with.”

As for what’s next, O’Neill is planning a new research project focused on eelgrass restoration, which will involve analyzing aerial footage of the Sound and the Peconic Estuary to establish a base map of eelgrass distribution. Eventually, this data will inform eelgrass management strategies and future research.

With increased interest in habitat restoration projects over the past few years, O’Neill is hopeful about the future of the field.

“Habitat restoration has come a long way in the 15 years that I have been in it,” said O’Neill. “Now, people can take undergraduate and graduate courses dedicated to restoration, individuals can become certified restoration specialists and project examples are bountiful throughout the country.”

But even with advancements and increased resources, the demand for habitat restoration work is increasing faster than staff members can keep up, especially as the impacts of climate change become more readily visible.

“It is still difficult to implement a habitat restoration project because they are costly and time-consuming,” said O’Neill. “On top of this, the urgency to implement projects, in a post-Hurricane Sandy world, is prevalent for practitioners in the New York area — this urgency can be felt throughout all coastal communities.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2023 edition of Interstate Waters magazine. Cheyenne Ellis is an information officer with NEIWPCC’s Communications and Outreach Division.