Are We There Yet? 1998 and Our Journey in Release Prevention

The year 1998 was filled with interesting events, such as the Denver Broncos winning back-to-back Super Bowls. Most underground storage tank (UST) owner/operators and many regulators remember December 22, 1998, as the deadline for compliance with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations. In late December 1998, I remember driving a U-Haul truck through a blizzard as we moved from Duluth, Minnesota to Denver and the following year, I began working in the tanks program with the state of Colorado.

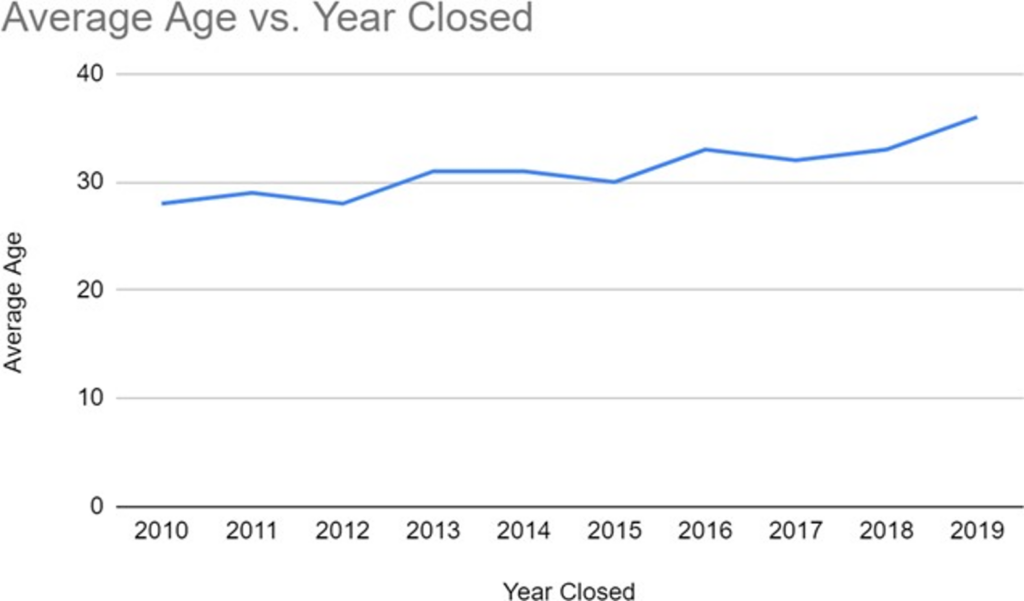

It is hard to believe it has been 26 years, and while we have seen a lot of improvements and changes in the tanks world, some things have stayed the same. In 1998 we were dealing with aging tanks, and now in 2024, many of the tanks installed to meet the 1998 deadline are approaching or have passed their 30-year mark. In fact, a recent EPA study indicated that tanks are staying in the ground longer with an average age of around 30 years. Like any other mechanical devices, as tank system components age, their risk of failure increases, which in turn increases the risk of a release of fuel products into the environment.

Thankfully, the UST provisions in the 2005 federal Energy Policy Act (EPAct) required significant changes to state and federal UST programs aimed at preventing releases. The UST provisions, among other things, included inspections, operator training, delivery prohibition, secondary containment and financial responsibility, and cleanup of releases that contain oxygenated fuel additives. Like many other states across the country, Colorado welcomed these changes as they strengthened our programs, ensuring new tank systems were more protective, operators more knowledgeable about their systems, and delivery prohibition provided an effective means to ensure and maintain significant operational compliance.

This was followed by the 2015 revisions to EPA’s UST regulations. The new tank standards and operational requirements to comply with these 2015 revisions continue to reduce the impact of releases from operating USTs across the country. Thanks to these revised regulations and updated publications such as the Petroleum Equipment Institutes RP1200 (Testing of UST Spill, Overfill, Leak Detection, and Secondary Containment), the annual functionality testing of release detection equipment and the three-year testing of spill buckets, containment sumps, and overfill prevention devices have not only ensured more protective systems, but have also enabled earlier detection of releases.

As of this year, more than half a million, or 90%, of UST release sites in the United States have been cleaned up and closed. However, around 62,000 releases nationwide are still in the cleanup pipeline. Even though this number is high, the good news is that many of the newer releases are being detected earlier and are often cleaned up more quickly and therefore cost less. These significant achievements of the national tanks program are the result of great partnership and collaboration between the EPA, the states, industry partners, and most importantly UST owner/operators, working together toward a common goal.

In line with the national regulatory changes over the past two decades, Colorado tried to be innovative as we expanded our efforts on release prevention. We preached, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure,” and we wanted to make sure we put our money where our mouth was. We began doing this in 2007 when we adopted the 2005 EPAct requirements and enabled our Petroleum Storage Tank Fund (PSTF) monies to be used to provide small incentives to owner/operators for significant operational compliance. This was only possible through legislation and strong collaboration with our Colorado Wyoming Petroleum Marketers Association (CWPMA). The incentives were in the form of a waiver of a $10,000 clean-up deductible if the owner had voluntarily installed under-dispenser containment, double-walled spill buckets, and tank removals.

Later, through additional legislation, we were able to expand the scope of incentives to upgrades and early testing of equipment to comply with EPA’s 2015 regulatory requirements. Our PSTF also began offering owner/operators up to $30,000 per facility for tank removal costs by reimbursing a dollar per gallon of tank volume removed. Because of the effectiveness of this incentive which resulted in the removal of several hundred tank systems, we are now upping the ante to $60,000 per facility, by offering two dollars per gallon of tank volume removed for tank systems installed prior to 2008 (before our double-walled requirements). Our hope is that this will motivate owner/operators to remove many of the older tank systems without a mandate and also lower the average age of tanks in the ground, which we equate to reduced risk of releases.

This past year, through continued collaboration with our CWPMA partners, legislation has given us the authority to be creative and use a percentage deductible in lieu of our standard $10,000 deductible on PSTF cleanup reimbursements. As I write this, we are considering adopting a 10% deduction from the first dollar spent through $100,000 and an additional 1% thereafter up to our fund’s maximum liability of $2 million. While having a $10,000 standard deductible is great, it does not benefit those owner/operators who were diligent with operational compliance and therefore had small releases that were detected early and cleaned up for less than our deductible. Queries of our database indicated that 61% of owner/operators with confirmed releases do not even apply for reimbursement from our PSTF, and we suspect many do not because their cleanup costs were below our deductible. Our data also indicated that 79% of the NFAs (No Further Actions) or cleanups closed between 2004 through 2023 cost less than $100,000, and only 1.8% cost more than $1 million. We hope this new percent deductible will be a further incentive to find and address releases quickly, reward efficient cleanups, and make more releases eligible for reimbursement, while imposing a small disincentive for ineffective, costly cleanups.

Looking back over the last 25 years, I think we all have reason to be proud of the national accomplishments of the tanks program in protecting soil and groundwater. There will continue to be development and innovative improvements in tank equipment construction, installation, and operation focused on release prevention. I suspect we will continue to see significant changes in policies related to the use of transportation fuels over the next few decades, driven by climate change and other concerns. How will this affect our tanks programs? I am currently working on legislation related to our program’s oversight of electric vehicle charging stations. Will gas stations become obsolete by 2050, as we will all be driving around in electric vehicles, or better yet, teleported? I do not know; some things change, and some stay the same as in our tanks programs today. As Yogi Berra says, “It is tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”