The Man Behind the Cartoons: Meet Hank Aho, L.U.S.T.Line’s Cartoonist Extraordinaire

For more than 30 years, LUSTLine has been dotted with cartoons poking fun at the complexities and intricacies of the world of underground storage tanks. From artistic renderings of tank workers grappling with on-the-job struggles to personifications of tanks reacting to the changing industry, LUSTLine cartoonist Hank Aho’s work has brought a recognizable and humorous flair to an otherwise dense and technical publication.

“Hank has an uncanny ability to personify the most unperson-like things using nothing more than pen, ink, and paper,” said Marcel Moreau, a petroleum storage specialist who has known Aho and his work for decades.

For Aho, drawing has always been second nature. “If I look back at any of my old school papers, they are all embellished with a variety of doodles,” he said.

By the time he enrolled at the University of Maine at Orono, Aho had decided to major in biology but made a point of supplementing his scientific studies with a number of art classes. After graduating, he embarked on a 37-year career with the Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), where he held a variety of roles focused on remediating hazardous waste.

A Career in Hazardous Waste Mitigation

Aho got his start in 1974 as a member of Maine’s Oil Spill Response Team out of the Portland field office.

The team was made up entirely of workers like himself who were new to the field. In this role, Aho monitored tankers that were moored in Casco Bay, while aboard a modified Webber’s Cove lobster boat. The state assembled a group of responders to locate and clean up oil spills along the state’s navigable surface waters.

“At the time, Maine felt that one of the biggest threats to the environment was surface oil spilled from tankers,” said Aho.

In addition, Aho and his team inspected tankers and oil-separators for compliance and manned the state’s oil spill response phone line, which required one of the six staff members to be on call 24/7.

One of Aho’s first marine surface water spills occurred late at night along Little Diamond Island in the bay. He responded to a call about a strong petroleum-like odor and immediately set off to investigate.

Armed only with flashlights, coveralls, and boots, Aho and another officer navigated their boat to the island and carefully scrambled over the rocks, barnacles, and seaweed piled along the shore. They immediately detected an odor and, upon surveying the water, spotted oil floating on top of the surface.

Though they could not see the full extent of the spill in the darkness, Aho and his colleague were concerned enough to request the activation of the oil response contractor, a costly procedure which involved the deployment of specialized tools and personnel. This proved to be the correct decision as the daylight soon revealed the significance of the spill.

But Aho soon found that not all cleanup efforts would be as straightforward. “One thing I learned in this field is that the cure is sometimes just as bad as the disease,” he said.

He witnessed this firsthand when he was called out to Little John Island in the bay to examine a slick of heavy black oil that had gotten stranded on the island’s seaward side. The scene was messy, with oil coating the nearby rocks, seaweed, and tidal pools. Soon after, a contractor arrived and surrounded the spill with a floating boom to help contain and slow the spread of oil. But this alone was not enough. The contractor also recommended stripping the affected area of all vegetation and power-washing the island’s rocks.

“What was left of the island’s impacted area afterwards was pretty much just bare rock, devoid of any vegetation,” he said.

Aho also witnessed firsthand the impacts of leaking underground storage tanks when he investigated a site in Readfield, which had reported a strong gasoline odor. He evaluated the water supply at a convenience store and examined a surface water well located in the basement. Under the lid, he discovered a layer of gasoline floating on top of the water. He then entered a nearby building’s fieldstone cellar to assess the magnitude of the leak and discovered gasoline coating the entire floor.

“I quickly notified the people in the building and asked them to turn off the furnace and power, before calling the fire department,” said Aho. “I was quite concerned that this could become a dangerous situation before it could be stabilized.” The source of the leak turned out to be a small crack in the 3,000-gallon UST, which had to be pumped and removed.

In 1979, Aho transferred to DEP’s Augusta office, where he was in charge of the DEP’s Oil Spill Research Program. One of his projects was to create a map of Casco Bay that identified vulnerable areas, such as clam flats, that could be at risk from oil spills. Other projects included the disposal of oil-soaked debris and researched the effects of dispersants used in clean-up efforts on marine intertidal zones.

Following the passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (commonly known as the Superfund Act, or CERCLA) in 1980, Aho managed and organized Maine’s new Uncontrolled Hazardous Substances Sites Program, which addressed threats to human health and the environment posed by abandoned hazardous substance contaminated sites. His responsibilities included overseeing a team of project managers and hiring contractors to remediate contaminated sites.

One of the sites he worked on was the Eastern Surplus Superfund on the banks of Meddybemps, which consisted of more than three acres of land near Meddybemps Lake and the Dennys River. The land was originally operated by the Eastern Surplus Company, who sold army surplus and salvage items. When it closed in the early 1980s, many artifacts were left behind, along with large amounts of contaminated soil and groundwater.

“The site was like a potpourri of hazardous waste,” said Aho. “The path we walked along during our initial inspection wound around drums of chemicals, small tanks, transformers, containers of calcium carbide, an old torpedo, and 5-gallon buckets of paints and other solvents.”

The EPA began the process of removing above-ground objects, excavating and disposing of contaminated soil and sediment, and remediating groundwater supplies. Though much progress has been made, these efforts are still continuing today.

Before his retirement in 2009, Aho found a way to integrate his passion for art into his career. Throughout his time with DEP, Aho doodled constantly in the margins of his notes and submitted an occasional cartoon to the department’s newsletter. When his long-time colleague David McCaskill heard from Moreau that LUSTLine was looking for an illustrator, he immediately thought of Aho.

“I brought this challenge up to Hank, and he agreed to take it on,” said McCaskill, who worked as a senior environmental engineer before retiring after 38 years with DEP. “What he did not know was how often I was going to walk up to his floor and pester him about the illustrations for my LUSTLine articles over the years.”

Joining Team LUSTLine

NEIWPCC began publishing LUSTLine in 1985 to communicate with state regulatory agencies across the country. Editor Ellen Frye, who worked on the publication until her retirement in 2020, found illustrations and humor to be unexpectedly helpful tools in conveying complex topics to the audience.

“It was truly a miracle to meet up with a cartoonist who actually understands the quirky world of regulators and petroleum storage systems,” wrote Frye in Issue #50 of LUSTLine. “There is nothing like a Hank cartoon to get us in the right frame of mind to crank out a new issue.”

For Aho, working on LUSTLine has been the perfect way for him to combine both his technical and artistic skills. He has now worked on more than 75 issues and has created hundreds of cartoons to accompany submitted articles.

“My objective is to provide drawings that support the article, add a little humor, and perhaps, act as a hook to get the reader interested in the piece,” said Aho.

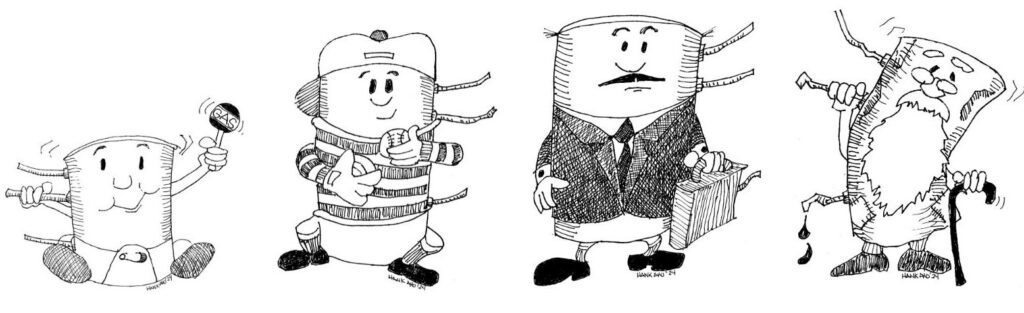

Throughout his time illustrating for LUSTLine, he has frequently created humanized underground storage tanks. From abandoned USTs shedding tears (Figure 5) to an angry tank ripping apart oil pipelines (Figure 6), Aho finds unique ways to bring the inanimate storage containers to life.

Moreau wrote a piece in Issue #41 that described the process of looking for answers as to why USTs ended up leaking. In return, Aho created a cartoon of a tank undergoing an autopsy (Figure 7).

In Issue #94, Aho created a cartoon based on the past, present, and future of the tanks program (Figure 9). “He illustrated the history of the tanks program from birth to maturity,” said Moreau. “Who else could have pulled this off so charmingly?”

While Aho excels in bringing to life unexpected components of the UST world, he is also successful at capturing the personalities of tanks workers and adding humor tailored to those who work in the field. In Issue #84, he created a cartoon of a frustrated tanks worker who has become fed up with the number of alarm messages produced by an automatic tank gauge (Figure 8).

“My characters are like my family,” said Aho. “I recognize them as my own unique style.”

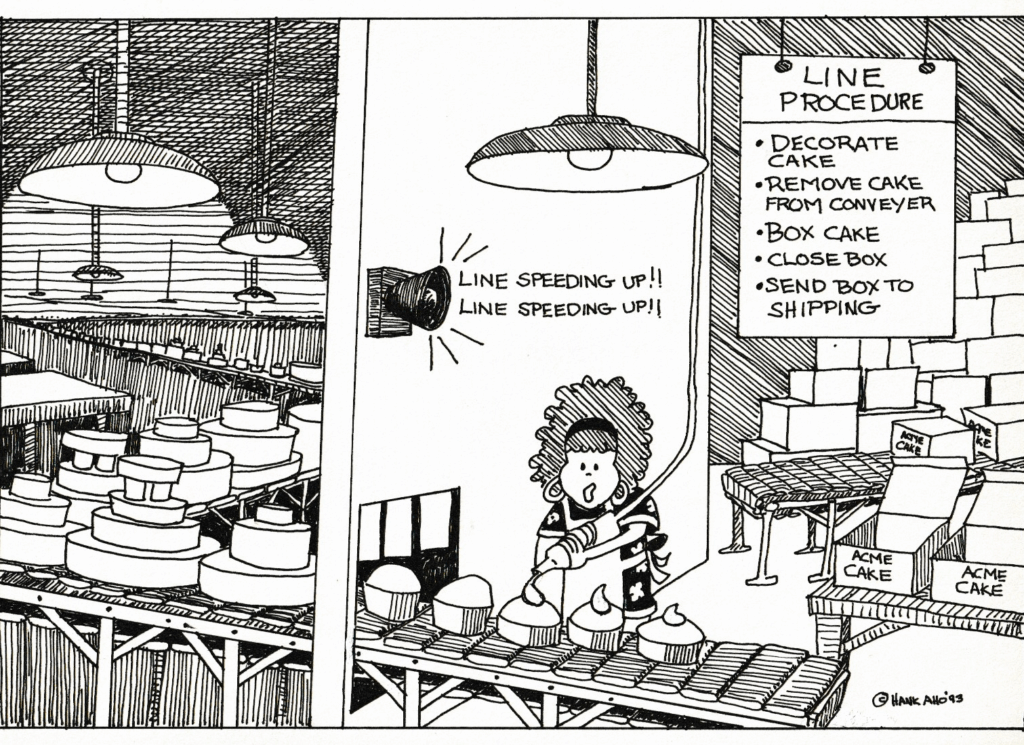

One of Aho’s favorite pieces is from the second issue that he worked on. In it, he created a cartoon reenacting a well-known episode of “I Love Lucy” where Lucy and Ethel take on a new job at a sweets factory (Figure 10). As the confections begin coming down the conveyer belt at an increasing speed, the quality of Lucy’s work decreases until she can no longer keep up. The article’s author uses this scene — and Hank’s recreation of it — to explain how tanks workers can feel when the number of leaking underground storage tanks in their area pile up.

Reflecting on how the industry has changed throughout his career, Aho noted that there is now much more awareness about tanks and the dangers that they pose. “It is important to keep stressing how beneficial tanks work has been, and how much still needs to be done,” he said.

Throughout his time with LUSTLine, Aho’s cartoons have certainly garnered a fan base among members of the tanks community, like Moreau, who look forward to seeing his witty interpretations of the articles when each new issue is published.

“Hank has added immeasurably to the content, readability, and enjoyability of LUSTLine for decades,” said Moreau. “His images stay with the reader long after the words themselves have faded from memory.”

To view more of Aho’s cartoons, click through the gallery below or browse through the LUSTLine archives.

Hank Aho lives happily retired on his family homestead in mid-coast Maine with his long-term partner Glenice, their dog Willie, and their boss cat Opie.