Tanks Program – Past, Present and Future

Past – Foundations of a National Tanks Program

What were you up to in 1984? Catching “Ghostbusters” and “Beverly Hills Cop” in theaters? Listening to “Footloose” and “Purple Rain” on repeat?

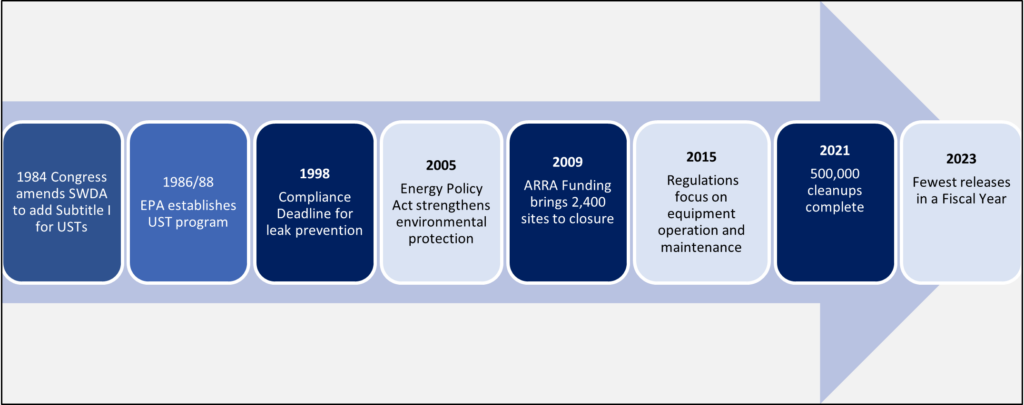

In 1984, Congress was laying the groundwork for the national tanks program. Congress amended the Solid Waste Disposal Act, adding Subtitle I, among other things, to protect the public from underground storage tank petroleum releases. Subtitle I directed the U.S. EPA to develop a regulatory program for USTs storing petroleum and certain hazardous substances.

The negative impacts of gasoline leaking from underground storage tanks were a growing concern for the U.S. population. One year before, in 1983, CBS’s “60 Minutes” aired the segment “Check the Water” that brought national attention to families in Canob Park, Rhode Island that were suffering from the effects of gasoline leaking from underground storage tanks. The local gas station had a leaking UST and gasoline had spread to soil and groundwater that was used as a drinking water source. Health, safety, and environmental concerns from petroleum and hazardous substance releases were in the spotlight.

In 1984, Congress took action and passed legislation that set forth definitions and exemptions, notification requirements, and instructed the EPA to develop UST regulations.

EPA had a lot of work to do in a short period of time to create a national program. It was quite an undertaking — from understanding the universe of tanks across the country, to working with owners and operators, states, Tribes, industry, and others to promote safety and environmental protection while providing flexibility for innovation and varying circumstances. Indeed, the immensity and complexity of the tanks universe at the time is summarized in the preamble to the 1988 regulations (see sidebar).

The Way We Were – The UST Universe in the 1980s

Faced with the mandate of Subtitle I, EPA recognized several unusual aspects of the regulated universe that have created special problems in developing an effective regulatory approach. First, the regulated universe is immense, including over 2 million UST systems estimated to be located at more than 700,000 facilities nationwide. Second, more than 75 percent of the existing systems are made of unprotected steel, a type of tank system proven to be the most likely to leak and thus create the greatest potential for health and environmental damage. Third, most of the facilities to be regulated are owned and operated by very small businesses, essentially mom and pop enterprises not accustomed to dealing with complex regulatory requirements. Fourth, numerous technological innovations and changes are now underway in various sectors of the UST system service community. – Preamble to 40 CFR Part 280, pg. 08. September 1988.

Building a program from the ground up included several rounds of public comment and public hearings, surveys and studies from the EPA and industry, and a series of draft regulations and guidance that covered prevention and cleanup requirements, state program approvals, and federal enforcement provisions.

In 1988, the EPA issued a broad set of regulations that set the structure for our modern-day tanks program. The regulations included technical requirements for leak detection, leak prevention, and corrective action. They also included financial responsibility requirements for UST owners and operators to demonstrate financial responsibility for taking corrective action, as well as compensating third parties for damage from releases from tanks containing petroleum.

The EPA set various deadlines for regulated UST owners and operators to comply with the 1988 regulatory requirements. Perhaps the most significant deadline was December of 1998. The EPA provided tank owners and operators 10 years to come into compliance with spill protection, overfill protection, and corrosion protection requirements, or to close their tanks. The catchy UST program slogan of “Don’t Wait Until 1998” served as a reminder and a warning. Upgrading, closing, or replacing tanks can be a costly and time-consuming effort. Missing the deadline could lead to violations, fines, and loss of insurance coverage.

The 1998 compliance deadline ushered in a new era of tank management. For the EPA’s UST prevention program, it was a very busy time for owners, operators, contractors, and regulators alike. Tanks had to be upgraded or safely closed. There was a palpable feeling that, despite the challenges, we were collectively making significant progress and tackling one of the nation’s most significant environmental challenges. Owners and operators that upgraded or replaced their tanks helped protect against petroleum releases into the environment. Thousands of old, sub-standard UST systems were permanently and properly closed. At the same time, thousands of contaminated properties were discovered and needed to be cleaned up. In fiscal year 1998 alone, 30,000 releases were reported. This flurry of activity ushered in a new era of UST system management that prioritized the safe storage of fuel underground. The following decades saw continued innovation in UST system management and an unwavering commitment to protecting human health and the environment from UST releases.

Present – We Have Come a Long Way

The UST program has continued to evolve and mature to the present day, tackling new challenges and formulating new solutions along the way. We have seen meaningful improvements in UST systems through the Energy Policy Act, the EPA’s 2015 regulations (and associated state regulations) and continued technical improvements and adaptations. This included navigating the migration to biofuels and the associated compatibility issues. The cleanup program continues to grow and evolve as we master the nuances of subsurface petroleum migration, assessment, and remediation.

Collectively, we have achieved tremendous results. The prevention program requirements continue to protect communities and groundwater, and each year we have tens of thousands of inspections completed. The UST cleanup program has addressed 90% of releases, with well over 500,000 cleanups completed and nearly 57,000 to go. As evidence of this great work with our many partners over the decades, there were fewer confirmed releases during fiscal year 2023 than during any other year in the program’s history, and we are on track to confirm even fewer releases this year.

Future – Who Knows What Tomorrow Will Bring?

As we turn our attention to the future, we must continue with our prevention and cleanup efforts. Aging tank infrastructure, natural disasters, and climate change add more layers of complexity for program planning and tank operations and maintenance. Meanwhile, we are seeing changes to the transportation sector, such as the emergence of electric vehicles and advances in fuel blends that will surely affect our program and UST owners and operators. It is hard to predict the UST landscape of the future. We must continue to work with our numerous partners, monitor trends, and develop new solutions as challenges evolve and emerge.

Conclusion

The tanks program has come a long way since 1984. Forty years later, we can look back in gratitude to our many partners who made the program a success and look forward to the challenges ahead. So many people have worked with the EPA to achieve our shared mission to protect human health and the environment. As long as fuel is stored underground, the regulatory and industry professionals in the UST industry will play a vital role in keeping our communities safe.

Were you involved in the tanks program in the ’80s? We would love to hear your UST and LUST stories from that time period. Please contact: James Plummer at NEIWPCC jplummer@neiwpcc.org or Mark Barolo at barolo.mark@epa.gov.