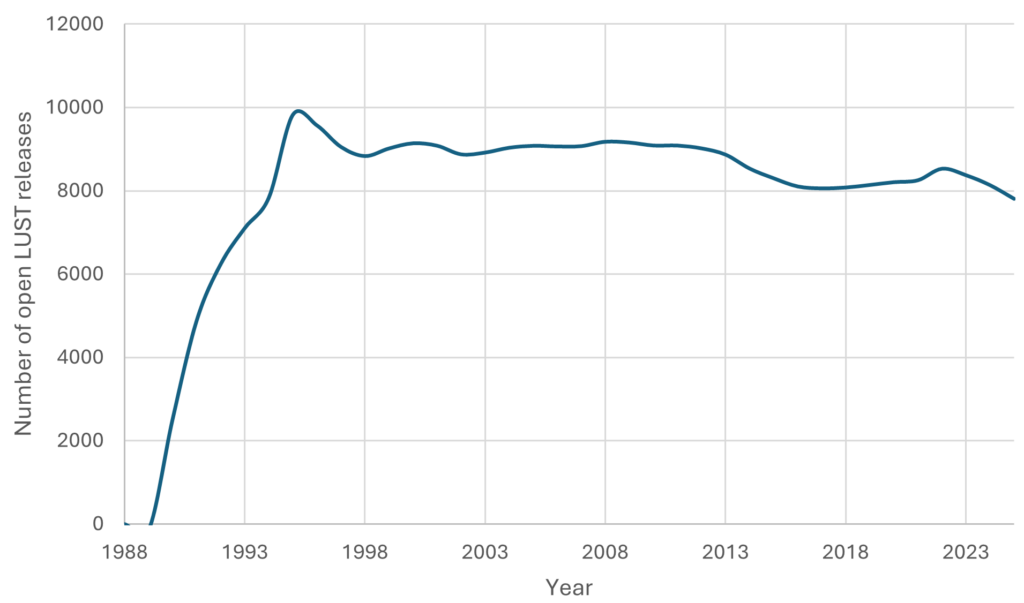

Michigan’s Backlog Story: Thirty Years with a Backlog of 8,000 Open LUST Releases

Introduction

In 1995, Michigan’s backlog climbed to more than 8,000 open LUST releases, where it remained for 30 years, not getting much higher, but not getting any lower. It was a steady backlog that was just a fact of life for the LUST universe in Michigan. It is something we have always had, and something that will always be there.

In 2020, following a few years of an increasing trend in our backlog, Michigan teamed up with the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Region 5 to undertake a backlog study to determine its root causes and potential solutions. Separate from this, Michigan convened an internal workgroup to determine obstacles to closure and potential solutions, and hired an outside expert in the ASTM International risk-based corrective action (RBCA) process to evaluate Michigan’s RBCA program. Here is what we found.

Evaluating the Backlog: Root Causes and Obstacles to Closure

Michigan’s backlog problem is not the result of a single factor. Rather, several factors have contributed over the years to a large and stagnant backlog.

Like many states in the 1990s, Michigan had a state reimbursement fund: the Michigan Underground Storage Tank Financial Assurance (MUSTFA). This fund was alive and well during the heyday of confirmed releases in the 1990s. But even though MUSTFA guaranteed reimbursement for cleanup, it soon became insolvent, leaving owners and operators on the hook for the costs of addressing thousands of releases. In 2014, a new reimbursement fund called the Michigan Underground Storage Tank Authority (MUSTA) was established; however, only releases that occurred after 2014 are eligible for reimbursement. More than 90% of open releases are therefore not eligible for MUSTA reimbursement.

In 1995, Michigan adopted a causation-based liability standard for LUST releases. The benefit of this was to provide a mechanism to encourage the redevelopment of contaminated properties without new owners taking on liability. While this has encouraged redevelopment, it presents a challenge for identifying parties liable to address LUST releases, particularly when releases remain open for 20 to 30 years.

In 2002, Michigan’s Storage Tank Division (STD) of the Department of Environmental Quality (now the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) merged with the Environmental Resource Division (ERD) to become the Remediation and Redevelopment Division (RRD), which still exists today. The STD had staff and processes that efficiently evaluated and addressed LUST releases. After the two divisions merged, there was a tendency to treat the LUST program (Part 213) the same as the non-LUST program (Part 201). Over time, the process to approve a single LUST closure went from a simple decision made by the project manager and supervisor to a process involving separate peer review groups for each technical issue related to the release.

In addition to the root causes of Michigan’s backlog as described above, the LUST program was also influenced in 2016 by the Flint water crisis, in which a series of events related to a change in the city of Flint’s drinking water source resulted in the population being exposed to lead in their municipal drinking water. Fingers were pointed in many directions for blame, and criminal charges (that were later dropped) were pressed against state regulators. Following this, the predominant decision on LUST closure report audits in the RRD was either “deny” or more frequently “insufficient information to make a decision.” While these results were supported by technical arguments, under the surface there was a hesitancy to approve a closure report unless an overwhelming amount of data supported it.

Concurrent with the EPA backlog study, the RRD convened an internal LUST workgroup tasked with determining obstacles to closure and potential solutions. The LUST workgroup polled RRD staff and determined that several obstacles to closures exist, including: an inefficient decision-making process for closures; requiring restrictive covenants for any contamination above Tier 1 Risk-Based Screening Levels (RBSLs) and often even below Tier 1 RBSLs; burdensome requirements for delineation; and an overly complex process for evaluating vapor intrusion. Recommendations from the workgroup include developing a more efficient decision-making process; making changes to restrictive covenant requirements; and simplifying RRD’s approach to vapor intrusion to align with what staff observe at sites.

An external review of Michigan’s RBCA program concluded that Michigan’s LUST program does not follow the ASTM RBCA process, despite the statutory requirement for a RBCA-based LUST program.

Addressing the Backlog: Solutions for Decades-Long Challenges

Just as the backlog was not caused by one single factor, the backlog problem cannot be solved by a single solution; rather, it must consider all aspects of the LUST program. The first step toward addressing the backlog was to establish a goal of obtaining 400 closures per year for five years. To achieve this goal, we had to develop tools for RRD staff and the regulated community to address the backlog. The tools we created are divided into four categories: 1) technical updates; 2) program and policy changes; 3) staffing and funding; and 4) culture change.

- Technical Updates

We updated guidance documents for all technical areas with the focus on making guidance align with the most recent science and field observations, be practical to implement, and be protective of public health and the environment. The biggest change was related to the practicality aspect. The RRD historically had numerous guidance documents that were technically and legally correct, but were often not practical to implement. In the area of vapor intrusion, we separated petroleum vapor intrusion (PVI) from nonpetroleum vapor intrusion and created a PVI guidance document that greatly simplifies RRD’s approach to vapor intrusion at petroleum LUST sites. The updated PVI guidance document emphasizes evaluating PVI risks using soil gas data rather than groundwater or soil data and aligns with the Interstate Technology and Regulatory Council’s PVI approach based on screening distances.

- Program and Policy Changes

In this broad category, the RRD district offices engaged in a letter-writing campaign to re-engage owners and operators at stalled LUST release sites. To help transition liable parties back into compliance, we developed a “compliance plan” option in which a party can commit to accomplishing certain activities with a schedule to return to compliance. Compliance plans have been a great success. Over 90% of parties that voluntarily submitted compliance plans have implemented the activities according to the proposed schedules.

To facilitate efficient decision making, we established a streamlined decision process in which a closure decision is made by the project manager in conjunction with the supervisor, rather than requiring a peer review group’s input on the decision. This change aligns with the historic STD decision-making process and is consistent with processes in other states.

One challenge with Michigan’s LUST statute, Part 213, is that it is written to specify a liable party’s obligations with respect to LUST releases but provides little direction regarding what EGLE can or cannot do, or how to bring a release to closure if there is no liable party. To provide guidance for EGLE staff, we established a new file review closure process. The process is a mechanism for EGLE staff to review site files, particularly legacy orphan LUST releases, and bring them to closure if warranted by the site data.

Regarding Michigan’s RBCA program, EGLE worked with an external consultant to develop a Michigan RBCA (MIRBCA) technical guidance document with accompanying report forms and computational software to develop Tier 2 Site-Specific Target Levels (SSTLs). Although Part 213 has referenced the ASTM RBCA process since the mid-1990s, Michigan did not have any guidance documents regarding how to implement the RBCA process or how to calculate SSTLs. The process outlined in the MIRBCA guidance document presents a paradigm change for implementing corrective actions in the LUST program, and we expect that this will greatly streamline LUST work after the regulated community and EGLE staff become familiar with the new approach.

- Staffing and Funding

The obvious solution in this category is to increase staffing and funding. We doubled the funding for EGLE’s triage program. This is a program where EGLE field geologists conduct a 1-to-2-day mobilization of ground-penetrating radar, soil borings, groundwater samples from temporary wells, and soil gas samples, often at orphan sites that have little data. Staffing in the LUST program also increased, but a more significant change was how staff are organized. Prior to 2024, project management staff split their time working on both LUST and non-LUST contaminated sites. To gain efficiency, we divided our project management staff by program, with staff in each office dedicated to either the LUST or the non-LUST program. “Tank teams” of project managers dedicated to LUST work were created in all ten district offices across the state. Project managers work independently on LUST sites but also collaborate with the team. Each district tank team has metrics based on the number of open releases in the district (more on this in the next section).

We created two critical new staff positions to help the overall division organization, as well as to provide leadership in addressing the LUST backlog. Technical specialists were reorganized into a new section (the Technical Support Section) with the Toxicology Unit, and a Section Manager position was created to provide leadership over the section and technical issues related to addressing the LUST backlog. A Part 213 (LUST) Program Coordinator position was also created to provide leadership for the LUST program and leadership over program and policy issues related to addressing the LUST backlog.

- Culture Change

Changing technical guidance, policies, and increasing and reorganizing staff are positive changes but are not likely to result in a significant decrease in the LUST backlog without changes to the underlying culture within the RRD. In the work culture, priorities were driven by reports from active sites that have statutory review deadlines, which can leave little time for project managers to evaluate stalled backlog sites. The report review process has historically focused on delineation and site characterization, even if the data is not used to make risk decisions or would not change a risk-based decision. The most common conclusion for a closure report audit was that there was insufficient information to make a determination. We were good at picking apart sites and reports and finding areas where more data would be useful. We are changing our approach, particularly with the legacy sites, to looking at the data and the receptors holistically for lines of evidence that would support release closure.

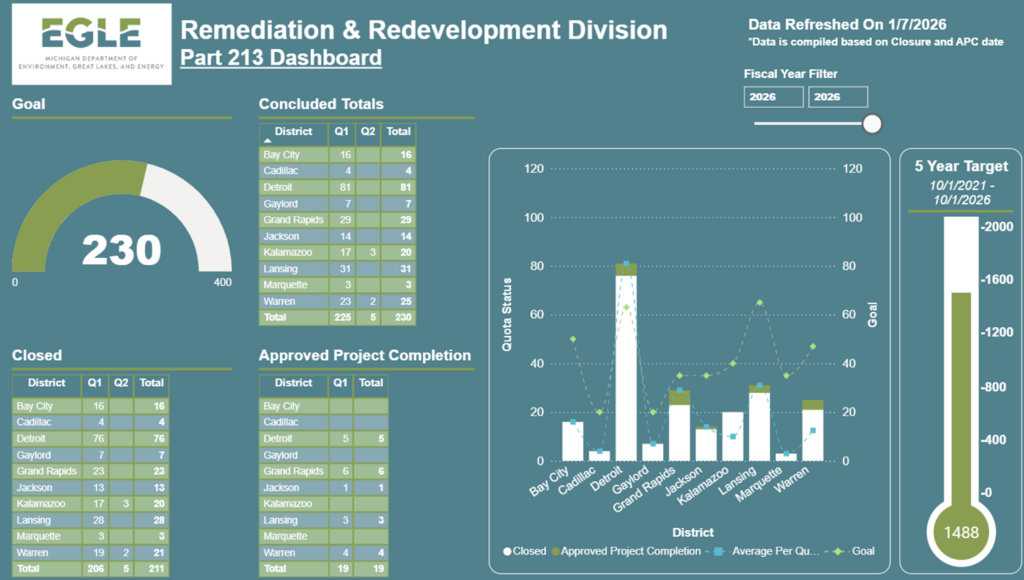

Culture is the hardest aspect of the LUST program to change and there are several ongoing efforts. In 2022, the RRD established a goal of closing 400 releases per year over a five-year period. Each of the 10 district offices has its own closure goal based on the number of open releases in the district. A dashboard was created on the RRD’s SharePoint page in a way that tracks each district’s progress and is visible for all districts and staff to see, providing both goals and accountability among the districts.

There is an ongoing effort to train staff and continually emphasize aspects of the petroleum lifecycle, including biodegradation, dissolved plume stability, and typical lengths for dissolved petroleum plumes. This gives LUST project managers starting assumptions about the site based on the nature of petroleum contamination rather than requiring data to prove something that can be reasonably assumed.

We are shifting the focus away from delineation and characterization and toward risk and asking questions about characterization. What decision will be made with newly requested data, and can that decision be made with the existing data? What is the exposure scenario that is being evaluated with the data?

Lastly, we are encouraging staff to use professional judgment. The new messaging is twofold. First, policies are written to address 80% of the common scenarios, and not all sites will fit perfectly into the policies. Staff should use judgment where it makes sense. And second, “risk” is the chance of an adverse health effect, which can occur only when a receptor is exposed to contamination. Exposure rarely occurs at typical LUST sites with current use and even in reasonable future exposure scenarios.

Results

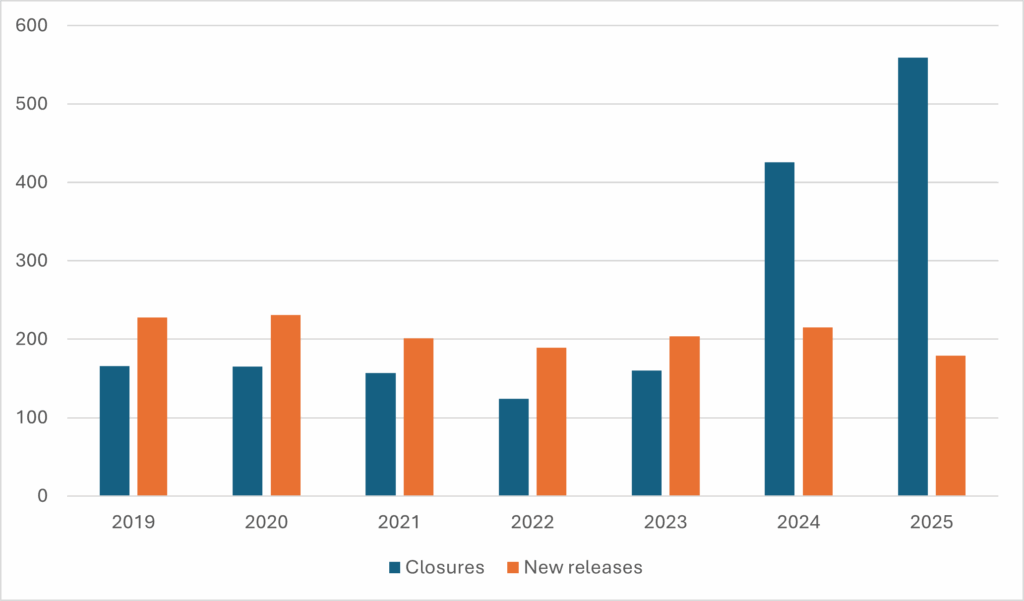

The efforts to evaluate the LUST program and reduce the backlog began in 2020, and the closure goals began in 2022. The efforts span across technical, program and policy, staffing and funding, and culture. The first few years of effort saw no change in the backlog, with closures continuing to lag behind the number of newly reported releases.

These efforts started to show results in 2024 when the annual closure goal was met for the first time with 426 closures. In 2025, the number of closures increased to 559. These numbers do not reflect the new MIRBCA program that was introduced late in 2025. Continuing this momentum and adding the new MIRBCA program, Michigan EGLE expects to see even greater number of closures in 2026 and beyond.