In 2013, NEIWPCC commissioned a study funded by the Long Island Sound Study to assess the feasibility of low-cost nitrogen removal retrofits to wastewater treatment plants in the upper Long Island Sound (LIS) watershed. The study, completed by JJ Environmental, LLC in 2015, presented a suite of cost-efficient retrofit and process modification recommendations for 21 plants in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont.

Five years later, NEIWPCC contacted the facilities to learn about any nitrogen removal upgrades and operational changes made since the study’s completion.

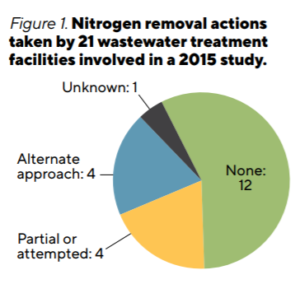

Of the 21 facilities included in the study, eight made some type of upgrade, of which half attempted to implement the study’s recommendations and the other half chose an alternate approach to the recommendations presented. Two of the facilities were required to make changes in order to meet permit requirements, while changes were voluntary at the other six. Twelve facilities made no changes, and one could not be reached.

Excess nitrogen has long been the dominant water quality concern in Long Island Sound. In 2001, the EPA approved a total maximum daily load (TMDL) for dissolved oxygen in LIS. Nitrogen pollution in the Sound reduces dissolved oxygen to unhealthy levels, and the TMDL is designed to reduce the amount of nitrogen reaching the Sound from both point and non-point sources throughout the LIS watershed, which includes portions of all the states in the Northeast except Maine.

The study created conceptual designs using BioWin simulations that took into account current facility configuration, operation and maintenance costs, and effluent nitrogen concentration to recommend the most practical, cost-effective upgrades. The report found that 20 facilities could improve nitrogen removal using low-cost retrofits, predicting additional nitrogen removal totaling about 2,313 pounds per day or 844,525 pounds per year at a capital cost of $5 million.

Of the eight facilities that attempted or partially implemented the study’s recommendations, the practices to achieve nitrogen reduction involved better control of dissolved oxygen levels at the facilities, including the addition of automatic controls and timers and installation of new variable frequency drives, pumps, aerators, and/or blowers.

Another plant began operating with simultaneous nitrification/denitrification, which is an accepted nitrogen removal strategy. Other facilities are undergoing complete upgrades which will include nitrogen optimization. Several facilities received supplemental funding from programs including the Massachusetts Clean Water State Revolving Fund, Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, and the Long Island Sound Futures Fund.

The study motivated one plant to implement changes, but it did not follow the recommendations due to higher-than-expected costs. To stay ahead of any possible mandates, that facility took an alternate approach, accomplishing nitrogen improvements with no increase in operating costs. Three facilities reported conducting additional studies on their own.

The study’s recommendations raised concerns for many facilities. Two of the plants tried to incorporate operational recommendations for several years but encountered problems. The reasons that others did not attempt the study’s recommendations included concerns over damage to the plant and reduced performance, significant maintenance requirements, and preference for more traditional treatment methods. The feedback suggests that future studies should combine computer-simulated design recommendations with on-the-ground experiences and include additional facility training or support to successfully implement recommended retrofits.

Permit requirements are the primary incentive for increased nutrient removal. For most facilities, any actions are entirely voluntary as they are meeting their current National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits. Most of the facilities’ permits require that they monitor and report total nitrogen concentrations in wastewater effluent, but do not specify a limit.

Little incentive exists to perform voluntary upgrades, although sometimes a plant can save money by changing its operation or is eligible for funding not available for meeting permit requirements. A host of barriers may deter action, including budget constraints, limited support from community leadership, and higher priorities for their limited funds such as addressing water quality contaminants of increased concern like PFAS/PFOA. However, several facilities are anticipating changes to their next five-year permit, at which time they will initiate changes to meet newly specified nitrogen limits.

A review of the study shows that it did influence wastewater treatment facilities, but with relatively minor reductions to nitrogen reaching the Sound. Our findings suggest that presenting facilities with a conceptual design and cost estimate per additional pound of potential nitrogen removal did not prove sufficient to spur action in most cases.

A more successful—albeit more costly approach—might include a comprehensive facility plan, including an iterative and adaptive implementation approach using more traditional treatment methods and providing funding for implementation.

by Audra Martin

Audra Martin is a former environmental analyst with NEIWPCC.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2021 issue of the “Interstate Waters” magazine. NEIWPCC remains committed to help improve water quality in Long Island Sound. For more information, contact Richard Friesner, director of the Water Quality Programs Division, at rfriesner@neiwpcc.org.