This past summer, NEIWPCC and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) hired a contractor to collect data on the density and habitat of American oyster (Crassostrea virginica) in the lower Hudson River. This Oyster Density and Sediment Characterization project sampled the oyster population between Piermont and Yonkers, New York, complementing prior studies to the north and south of this approximately 10-mile area. The information gathered will be used by the Hudson River Estuary Program to help inform future oyster restoration efforts.

Once abundant in the Hudson River, oysters suffered a significant population decline by the early 20th century due to overharvesting and sediment and water pollution. Now, with improved water quality, community and science-based organizations in the Hudson River watershed – such as the Billion Oyster Project – are working to restore the bivalves and the environmental benefits that they provide. Oysters filter excess nutrients from the water, while their reefs provide essential habitat and support local food webs.

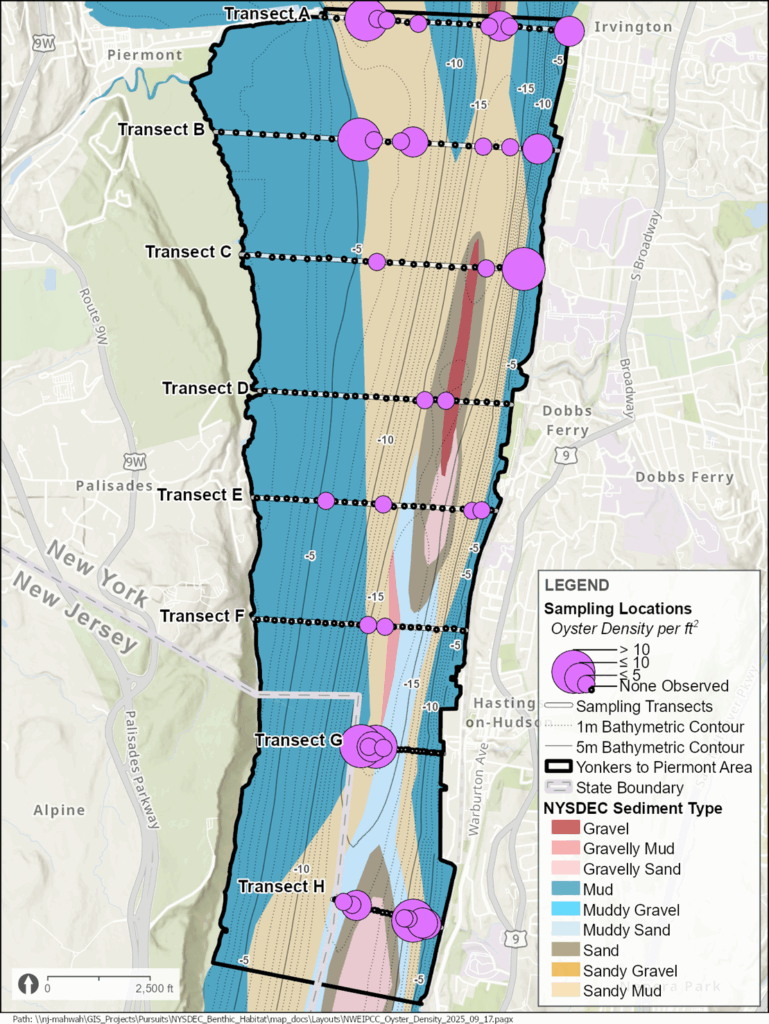

NEIWPCC hired Henningson, Durham and Richardson Architecture and Engineering (HDR), who specialize in environmental services and have experience in the Hudson River including habitat assessment and evaluation to complete the project. The HDR technicians conducted field work over the course of eight days in June and July while following an approved quality assurance project plan to ensure accuracy and reliability of the data. This work included collecting 1 x 1 meter bottom samples along eight designated study transects, which ran from east to west – perpendicular to the river flow. Twenty-five evenly spaced grab samples were collected along each transect, for a total of 200 samples.

Dan Miller, NEIWPCC environmental analyst and Hudson River Estuary Program habitat restoration coordinator, oversaw the project and explained the sampling methodology that the project team adopted. “We wanted to cover as much of the area as possible to look at the distribution and where oysters occur. By having evenly spaced transects with the same number of samples within the transect, we have an even grid of data over the entire portion of the river included in the survey.”

Working by boat, HDR technicians used a crane to lower a small dredge to collect oysters and sediment from the river bottom. A winch raised the sample onto the boat’s deck, where the researchers then measured the contents to ensure an adequate sample size was extracted.

The sediment was categorized into mud, sand and gravel categories, following the classification rubric from previous oyster sampling work in the Hudson River. Using a sieve, the researchers then isolated the collected live oysters and shells to count and measure them before returning them to the river.

“This type of work is like a mix of commercial fishing and science,” said Miller, who joined the HDR team to perform a quality assurance field assessment. He said teamwork, innovation and dexterity were essential while working with heavy equipment in a small space. “When you see an operation like this, there’s a lot of science going on, but there’s also a lot of problem-solving and just making things right with the equipment. On one hand, you’ve got high precision instruments that are measuring water quality and position, and on the other hand, you have this very heavy dredge to pull up in a physical, inelegant process.”

In addition to the grab samples, side-scan sonar imagery was recorded along each transect to map seabed features and to better characterize the habitat that was sampled. Water quality data including salinity, temperature, and dissolved oxygen were also collected, along with water depth, to identify habitat conditions and potential preferences for oysters in this region of the river.

The survey found that oyster density ranged from zero to 28 oysters per square foot and was generally higher near the northern and southern portions of the study area. Additionally, oysters were most commonly found, and in higher densities, in sandy mud sediment.

The project contributes to the baseline understanding of oyster presence in the Hudson River – an important first step in planning restoration efforts. It also supported the Hudson River Estuary Action Agenda, a conservation and restoration blueprint developed by the NYSDEC, that includes a goal to improve oyster habitat. Researchers and environmental managers hope to merge the data collected with the data from the other surveys to the north and south to create a continuous map of presence/absence of oysters and the conditions that they prefer.

“From this mapping effort, and the efforts to the north and south, we know the places where we are more likely to find oysters,” said Miller. “These areas are like signposts saying, ‘oysters like it here’ and could be a good spot for future restoration efforts.”

The final project report is available in NEIWPCC’s Resource Library.