Two dams that stand between Atlantic salmon and upstream spawning habitat on the Saranac River in New York are coming down, the culmination of years of collaboration among the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Trout Unlimited and other public-private partners. The Lake Champlain Basin Program supported the project by providing $370,000 in funding through its Aquatic Organism Passage Implementation Fund, provided under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

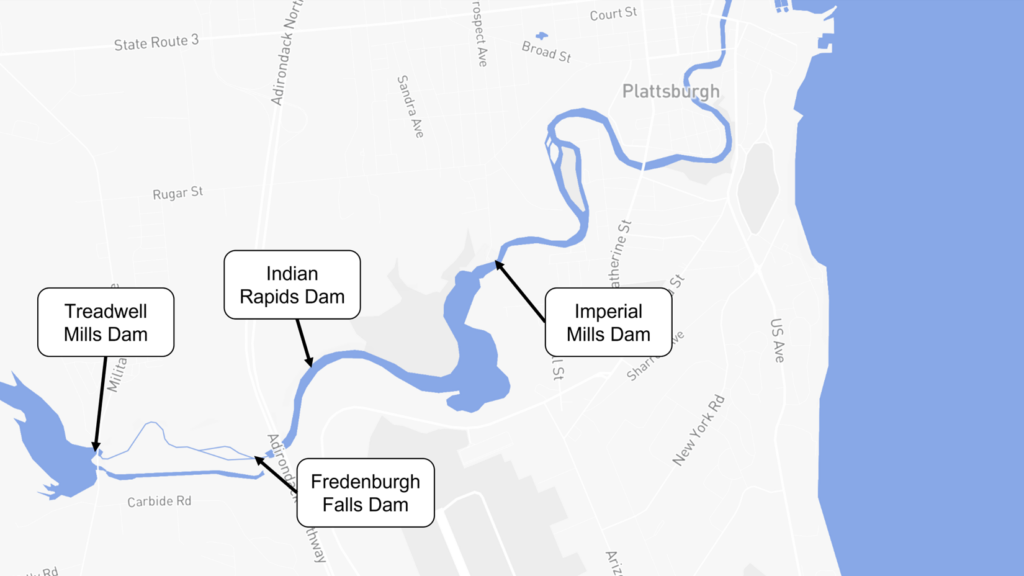

The removal of the Indian Rapids and Fredenburgh Falls dams advances a conservation goal more than three decades in the making: reestablishing salmon runs in the largest tributary on the New York side of Lake Champlain.

“Our goal is to have a healthy river where the salmon can once again reach their natal spawning waters,” said Rich Redman of the Trout Unlimited Lake Champlain Chapter, a long-time advocate for restoring the fishery. “The removal of the remnants of these dams is an important piece of that effort.”

Ancestral home

The Saranac River is one of four tributaries in the basin where the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is prioritizing efforts to restore wild salmon populations, including by removing barriers that prevent them from completing their life cycles.

“Before dams were built on the lower Saranac River, Atlantic salmon had been migrating up this river to spawn for thousands of years,” said David Minkoff, a fish biologist at the Lake Champlain Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office.

In the early 1800s, Dewitt Clinton, a naturalist who would go on to become New York’s governor, reported in his “Letters on the Natural History and Internal Resources of the State of New York” that these fish had once been so numerous, fording the river at Plattsburgh was considered dangerous because horses would startle at “the darting of the salmon through the water.”

“Thanks to decades of restoration work, salmon are once again returning to the Saranac River, and the removal of these remnant dams is vital for reestablishing access to historic spawning and nursery habitat,” said Minkoff.

Once the Indian Rapids and Fredenburgh Falls dams are gone, only the first obstacle on the river — the Imperial Mills Dam — will stand between Atlantic salmon and upstream habitat that has been inaccessible since 1786, when the first dam was constructed across the lower Saranac River.

Setting the stage for a salmon comeback

In the 1980s, fish-passage requirements for new hydroelectric development at existing dams in the lower Saranac River made restoration of Atlantic salmon in the Saranac River appear imminent.

Lower Saranac Hydro Partners, now owned by Patriot Hydro, installed a fish ladder at the Treadwell Mills Dam — a hydro-power facility upstream from the Indian Rapids and Fredenburgh Falls dams— as part of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) relicensing process for generating electricity at the site in 1990. Lower Saranac Hydro also entered into a settlement agreement to remove the Indian Rapids and Fredenburgh Falls dams.

However, the hydroelectric development proposed at Imperial Mills Dam, the first barrier on the Saranac River, and its required fish ladder, were never constructed. The lack of fish passage at Imperial Mills resulted in an agreement to delay the removal of the dams and eventually turn off the fish ladder at Treadwell Mills. So far, salmon have never been able to use the ladder at Treadwell Mills because of the three barriers downstream.

But that’s about to change.

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation has taken over the task of installing a fish ladder at the Imperial Mills Dam. The fish ladder is slated for completion by fall of 2026. Patriot Hydro is currently pursuing a FERC relicensing of their hydroelectric project at the Treadwell Mills Dam.

SLR Consulting signed on to lead the on-site engineering and construction, including coordinating with state and federal agencies on surveys for imperiled species.

Now, after years of planning and coordination, the dams are coming down, and Atlantic salmon will soon be able to access 13 miles of spawning habitat on the river’s mainstem, and another 18 miles on tributaries, for the first time since around the time of the American Revolution.

There is pent-up demand: A large run of salmon backs up at the base of the Imperial Mills Dam each fall, an indicator of the success of the ongoing effort to restore this species in Lake Champlain and of the resulting need for more spawning habitat.

The Service and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation will study the migration of these freed Saranac salmon, both through the efforts of our Lake Champlain Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office fisheries program and through the New York Field Office-led studies of the Treadwell Mills Dam fish ladder, to ensure that the population continues to recover.

Ripple effects for people

The removal of these dams will also benefit people who live in communities along the Saranac River, as well as those who are drawn to the river for recreation.

The Indian Rapids Dam has long been a barrier for the Northern Forest Canoe Trail, a 740-mile trail that follows historic waterways from Old Forge, New York, to Fort Kent, Maine. Although the dam was partially breached in the 1950s for safety reasons, it represents a hazard for paddlers, funneling fast-moving water through a channel over an eight-foot drop between concrete piers.

The dam remnants also increase flooding risks by creating an artificial bottleneck in the river.

While little of the spillway remains at the site of the Fredenburgh Falls Dam, large steel A-frames and embedded timber cribbing remain in the river, interfering with fish passage and natural stream function and detracting from the appearance of the area.

Removing this remnant infrastructure will restore the natural look and flow of the river at these two sites.

Long-awaited homecoming

This historic win for people and wildlife has been a long time coming. In 1786, the state of New York sued Zephaniah Platt, the owner of the first mill dam constructed across the lower Saranac River, on behalf of local fishermen in upstream communities who could no longer catch the salmon they depended on for their sustenance and livelihoods.

The fishing community lost that lawsuit nearly 250 years ago, but conservation partners are on the case today.

In just a few years, salmon will be able to return to the upstream habitat where their ancestors spawned, and a new generation of anglers will follow.

For more information see the USFWS press release.