This article was originally published in the July 2021 issue (#89) of “LUSTLine,” NEIWPCC’s twice-annual news bulletin for the underground storage tank community.

Preparing for a Radically Different Future of Fueling

Four trends will profoundly shape the future of the gas station industry and associated federal programs, which insure and regulate USTs in the U.S.: the rise of electric vehicles (EVs), the consolidation of gasoline retailing, the aging of USTs, and increased regulation and political pressure surrounding gas stations.

The Phasing out of Gasoline Powered Cars and the Rise of Electric Vehicles

Governments around the world are working to phase out the sale of gasoline-powered vehicles in an all-out effort to stave off the worst effects of climate change. Eighteen countries are planning to stop the sale of new gasoline powered vehicles between 2025- 2040, and their numbers are growing

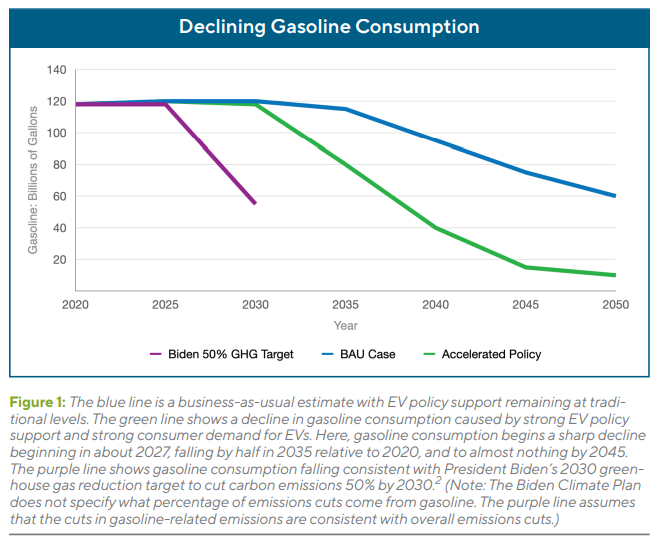

In the U.S., gasoline combustion makes up about 17% of all carbon emissions. California, Massachusetts, and New York have all announced plans or targets to phase out the sale of new gas cars by 2035, and the Washington State legislature recently voted to set a goal to phase them out by 2030. The Biden Administration’s infrastructure plan proposes to spend $170 billion on speeding the transition to electric vehicles, and its climate plan calls for carbon emissions cuts of 50% by 2030, cuts which will necessitate broad reductions in gasoline use.

Industry is joining the rush to move beyond gasoline. General Motors has announced that they will sell only EVs after 2035, and Ford has said that they will sell only EVs in Europe after 2030. Jaguar, Volvo, and Honda have announced plans to phase out the sales of gas cars in the U.S. by 2025, 2030, and 2040, respectively. Numerous automakers have announced that they will stop developing new gasoline engines.

Automakers are rapidly increasing their offerings of electric models to meet anticipated demand. The base electric version of the Ford F-150, America’s bestselling vehicle, will go on sale in May 2022 at a price under $40,000. The Ford Mustang Mach-E SUV was released this spring and is available for about $43,000. A raft of new EV offerings is expected in the coming years. The sticker prices of new EVs are expected to be at or below the price of comparable gasoline vehicles by the mid-2020s, further accelerating the shift towards EVs1.

While the shift to EVs now appears inevitable, the effect that the shift will have on nearto-medium term gasoline sales is unclear. Of the 280 million light duty vehicles on U.S. roads, fewer than 2 million are EVs. Only about 6% of the entire vehicle fleet turns over every year, signifying that it could take until 2035 or later for the majority of vehicles on U.S. roads to be electric, unless “cash for clunker” style policies begin to take more gas cars off the road.

Consolidation of Gasoline Retailing

The challenge to gas stations isn’t only stemming from EVs. Large retailers such as Costco and Kroger are rapidly building very large 25+ pump gas stations in many parts of the country. These retailers can underprice smaller gas stations by 10% or more and can sell as much as 20 million gallons a year, or 20 times as much as traditional gas stations. Consolidation of smaller and independent gas stations into chains of 50 or more retailers is also underway. These trends will likely increasingly squeeze the margins of independent gas stations.

Aging of Underground Storage Tanks

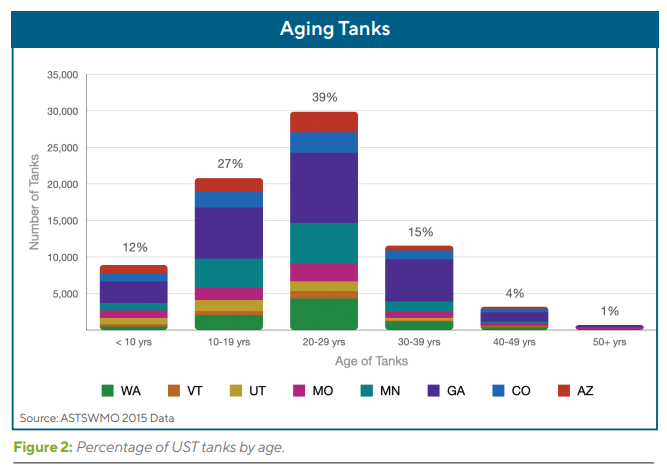

Meanwhile, there is a ticking time bomb in the ground. It is now about 30 years on from the wave of UST replacements that occurred in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The average tank in the U.S. is more than 25 years of age and nearing the end of its warranty (typically 25-30 years). Many private insurers refuse to insure tanks older than 25 years or require much higher premiums and deductibles. According to Lockton, a leading insurance broker for USTs, “the [insurance] industry views the average useful life span of tanks between 26 and 30 years. Depending on soil conditions, the useful life may be shorter or longer, but it is known that as the tank ages, the likelihood the system is leaking grows exponentially.”3

Many gas station owners and operators are facing higher operational, maintenance, and inspection costs due to new regulatory requirements and unanticipated equipment degradation. Figure 2 shows percentages of UST tanks by age in nine U.S. states, indicating that 20% of USTs exceeded 30 years of age in 2015.

The extent of the liabilities for UST funds in connection with aging tanks usually remains unknown and unbooked until there is a sale, financing, or change of use for the gas station triggering a phase 2 assessment. When gas stations start going out of business, many more environmental liabilities may surface as former gas station sites change hands.

Increased Regulatory and Political Pressures on Gasoline Retailing

Gas stations are coming under increased political pressure from climate and environmental activists.4 Gasoline is the single leading source of CO2 emissions in the U.S., and people are increasingly concerned about the health and climate impacts of gas stations.

Environmental justice advocates are taking a hard look at gas stations, which are more likely to be located in Black communities. Leaking tanks have also been found to be more prevalent in Black communities.5 Regulators should expect increasing pressure from Black and brown communities6 to clean up older gas stations. They should also expect less tolerance of gas station pollution, especially as the powerful health effects of gas station pollution become more widely known.7

The Future of Gas Stations

These trends add up to a bleak future for most gas stations, particularly independently owned stations with older tanks and those selling smaller volumes of gasoline. Sales volumes will likely decline with gathering speed as EVs take increasing market share while margins are increasingly squeezed by larger players. Boston Consulting Group has forecast that as many as 80% of gas stations could be unprofitable by 2035.8 Meanwhile, gas stations are faced with imminent large investments in new USTs and the cleanups that often occur when the USTs are replaced. With the long-term revenue forecast for gas stations increasingly murky, lender financing for new USTs and cleanups is very much in doubt.

The number of gas stations in the U.S. has declined by about 20% in the last 20 years. Half of the brownfields in the U.S. are impacted by petroleum, a substantial share of which are shuttered gas stations.9

UST Funds in the EV

Era Just as a drop in gasoline sales will cause major revenue shortfalls for UST funds, a wave of gas station closures is likely to trigger expensive cleanup demands. This trend will likely begin accelerating in the mid-to-late 2020s and speed up from there as older stations face declining sales and lower margins and close their tanks. Some states experienced this on a small scale with COVID-19, when gas sales were down, and some stations went out of business. The difference with the EV takeover is that sales will never bounce back, but rather continue an ever-steeper path of decline.

Unless swift action is taken, USTs fund managers will face a huge increase in claims driven by gas station bankruptcies and demands to clean up long-neglected gas stations, especially in communities of color. Meanwhile, elected officials may be reluctant to raise gas taxes to pay for the skyrocketing costs because of political sensitivities around fuel tax increases.10

Preparing for the Change

Regulators and fund managers need to evaluate their programs in light of the rise of EVs, industry consolidation, the aging of USTs, and increased regulatory and political pressure around gas stations.

For example, how would a tank fund handle a scenario where fund revenue declines by 2% a year, and fund costs driven by closing gas stations rise by 10% a year starting in 2025?

Key stakeholders such as affected government agencies, gas station owners, environmental groups, and elected officials should be brought to the table now to understand where EVs and tank insurance finance are headed, and to participate in planning for and implementing a smooth phaseout of gasoline sales. These steps will likely involve increasing revenue to the fund and eliminating the oldest, highest-risk USTs from fund coverage.

Matthew Metz is the founder and co-executive director of Coltura. Reach him at matthew@coltura.org.

Endnotes

1. See e.g., Jasper Jolly, Electric cars ‘as cheap to manufacture’ as regular models by 2024, The Guardian, October 21, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/oct/21/ electric-cars-as-cheap-to-manufacture-as-regular-models-by-2024

2. The White House, Fact Sheet: President Biden Sets 2030 Greenhouse Gas Pollution Reduction Target Aimed at Creating Good-Paying Union Jobs and Securing U.S. Leadership on Clean Energy Technologies, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/ statements-releases/2021/04/22/fact-sheetpresident-biden-sets-2030-greenhouse-gaspollution-reduction-target-aimed-at-creatinggood-paying-union-jobs-and-securing-u-sleadership-on-clean-energy-technologies/

3. https://www.lockton.com/whitepapers/Underground_Storage_Tanks.pdf

4. See e.g. Bill McKibben, “Do We Actually Need More Gas Stations,” The New Yorker, March 24, 2021, https://www.newyorker.com/news/annalsof-a-warming-planet/do-we-actually-need-more-gas-stations; Carrington J. Tatum, “Prospect Park residents take fight with gas station developer public”

MLK 50, November 13, 2020, https://mlk50. com/2020/11/13/prospect-park-residents-takefight-with-gas-station-developer-public/

5. Andre Perry et al., Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings & Gallup, The Devaluation of Assets in Black Neighborhoods: The Case of Residential Property 4 (2018), https://www.brookings.edu/ wp-content/uploads/2018/11/2018.11_BrookingsMetro_Devaluation-Assets-Black-Neighborhoods_final.pdf

6. Sacoby Wilson et al., Leaking Underground Storage Tanks and Environmental Injustice: Is There a Hidden and Unequal Threat to Public Health in South Carolina?, 6 Env’t Just. 175 (2013), available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC3980862/

7. See e.g., Marcus, Michelle. “Going beneath the surface: Petroleum pollution, regulation, and health.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 13, no. 1 (2021): 1-37. ;Metz, Matthew N., and Janelle London. “Governing the Gasoline Spigot: Gas Stations and the Transition away from Gasoline.” Envtl. L. Rep. 51 (2021): 10054, available at https://static1.squarespace. com/static/5888d6bad2b857a30238e864/t/5 ff87f254b02af23c9d904b8/1610121062028/ Governing+the+gasoline+spigot.pdf

8. https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/servicestations-future

9. https://www.epa.gov/ust/petroleum-brownfields

10. The federal gas tax hasn’t been raised since 1993 despite fund shortfalls, an indication of the political challenges associated with raising fuel taxes. See e.g. Institute of Taxation and Economic Policy, “It’s Been 10,000 Days Since the Federal Government Raised the Gas Tax,” February 21, 2021; Available at https://itep.org/its-been10000-days-since-the-federal-governmentraised-the-gas-tax/